The Illusion of Breath

Harold started me off on Chopin's little E Minor Prélude, the one that Jack Nicholson so memorably butchers in the movie Five Easy Pieces. It's not—as I learned that day—all that easy a piece. I don't believe we got past the first two measures in the first half-hour of the lesson. There's the relationship of the first note to the shorter note an octave above it, leading to the long sustained note—three different volume levels for those three notes; and then the repeated notes in the left hand, the lowest of which should be stronger than the other two; and although they're written as even eighth notes, they're not static, but subject to the push and pull of rubato (what Chopin meant by his “espressivo”) and the decline and swell that supports the melody. In fact, no two notes have the same volume level or the same duration, each dependent on its relationship to the others.

This illustrates the drawback to Harold's approach to music—its great virtue in terms of musical result, but its drawback for the performer. When I studied with my first teacher, things were so much simpler! Learn the notes, follow the composer's indications about tempo and dynamics, trust a bit in your own musicality, and you were home free. Under Harold's tutelage, you learned that there were so many more things to get right—you had a kind of three-dimensional awareness of each note's place in the music's universe—and thus so many more ways to get things wrong.

"Intentionality" is not a word he ever used, that I can remember, but it's a decent way to sum up his teaching: there's an intention to every element of the music; every note is going somewhere, it exists in a dynamic relationship with the notes around it, those before and after it, and those in harmony or disharmony with it. The scores are littered with arrows—these notes aren't just sitting there, they're going someplace.

His teaching, to use another fashionable term, explored music at the granular level, the level of the finest distinctions of nuance. Which, one learned, is where the essence of the music is to be found. Just today I came across this piece of academic musical analysis, saying that Schubert's song cycle Winterreise is structured around “a tonal core, on both sides of which are disposed songs in complementary, contrasting keys.” No doubt true, and no doubt a technique readily available to absolutely anyone writing a song cycle. You will not discover Schubert's genius at that level of scrutiny.

The teaching happened, when I first started taking lessons, in the basement of his parents' house, on what I remember as a large, ugly, old black Steinway. I'm sure that neither the piano nor the room's acoustics were ideal, but if you could make a piano sing, that piano would in fact sing. Which gets to the heart of the problem for any pianist: pianos are percussion instruments. After the hammer passes its release point in the action, it is sailing through the air free of any control from the pianist. After it strikes the string, the string's vibrations will gradually disperse, also out of the pianist's control. (Although you can get a small swell sometimes by stepping on the sustain pedal after the note has sounded.)

To make music breathe comes naturally to a singer, or, say, a clarinetist, where breath controls the sound and breathing determines phrasing. The pianist can only accomplish this through illusion, by the tiny gradations of volume and duration that Harold was teaching me in the Chopin E Minor. It's easy to imagine a singer with that long note in the first whole measure, holding it out and swelling it through to beginning of the next measure. But for the pianist, the note is dying once it is struck. Luckily, Chopin provides the left hand's throbbing accompaniment to give the illusion of lifting and carrying it along. Jack Nicholson can play the notes, but he can't carry, so to speak, the tune. The tune, to be carried, to be given the illusion of breath, must be given shape or contour (more of Harold's favorite words), indicated in these scores by great scrawling, looping outlines.

One of Harold's key insights was that a process of tension and release, generally approaching and leaving each bar line, was central to making music breathe, to giving it organic flow. This became such a frequent instruction that my fellow student Carol Christian and I gave him a set of rubber stamps, one of which was just a crescendo, a barline, and a diminuendo.

Another part of the granular attention he paid to a score was in his awareness of counterpoint. Not just the obvious counterpoint of a Bach fugue, but the subtle counter melodies, sometimes seemingly buried in the texture of the music. You will see a scrawled CPT! frequently on the scores. A profound musical experience I still remember occurred during a lesson on a Brahms Intermezzo. I had prepared it in the sense that I had learned to navigate the notes. When I was unable to articulate a bit of imitation in the left hand, Harold shooed me aside and simply played it for me. That counter melody came singing seemingly out of nowhere and sent, as they say, chills down my spine.

The scores include other, more mundane, notations: wrong notes circled, fingerings specified, instrumental suggestions: Harold was sensitive to orchestral implications in music, and would write “plucked” or “cello” or just “color” where appropriate. He seems to have written “leggero” (“light”) with some frequency—I'm not sure if everyone got that, or if I tended to be heavy-handed. “Pointed” is another frequent annotation—asking that a line be brought out with crystal clarity—think Horowitz, all of whose notes were pointed.

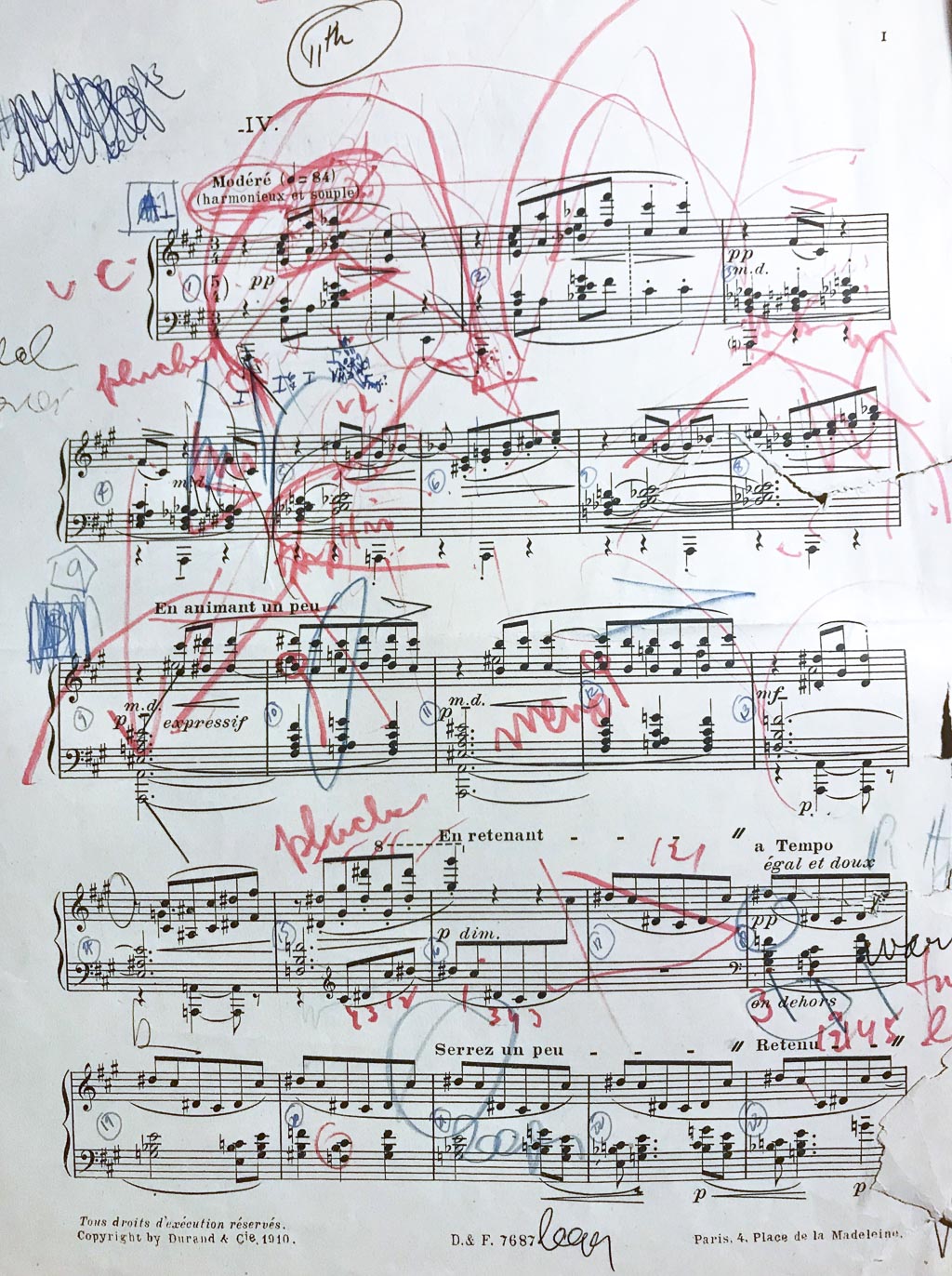

Debussy, Prélude, Les sons et les parfums

The score provides a good example of what Harold meant by “contour”, with great looping red lines emphasizing the shapes of the phrases. The difficulty here is that the phrase must be described with graduated intensities, rising then falling, in the span of seven notes, but all within the narrow range of pianissimo. He has written “UC” for una corda, soft pedal, to help out. He was in general not shy about recommending the una corda not just for softness but also for textural variety. I see that he has also noted “11th” at the top of the score, since that interval—a D# over an A major chord—is crucial to the piece. NB. This is one of the reasons Charlie Parker liked Debussy: they both liked to construct melodies using the upper reaches of the chords, the 9ths, 11ths, 13ths.

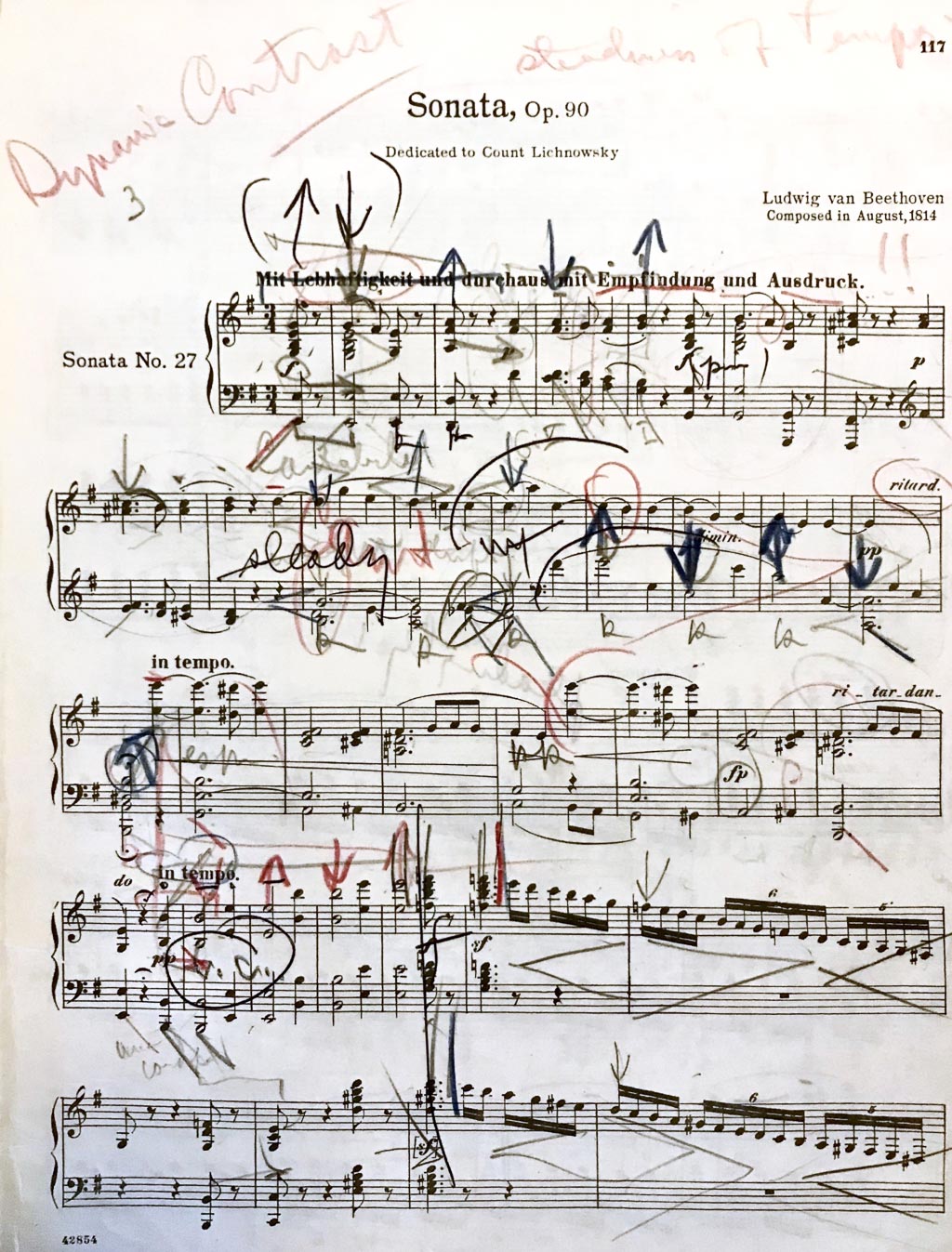

Beethoven, Sonata, Op. 90

He has outlined the first phrase, which is a kind of building block of the movement. He indicates its rhythmic forcefulness with arrows indicating downbeat and upbeat, asking that both be emphasized, but the upbeat as a release from the force of the downbeat. Above the contrasting section (Harold has written “Dynamic Contrast” at the top of the page) which follows (m. 9) is written “Cantabile”—singing, and he marks out the left hand's counter-melody in the second half of the phrase. A the bottom of the page, some of his favorite crescendos and diminuendos leading to and from bar lines: music is never static, least of all in Beethoven.

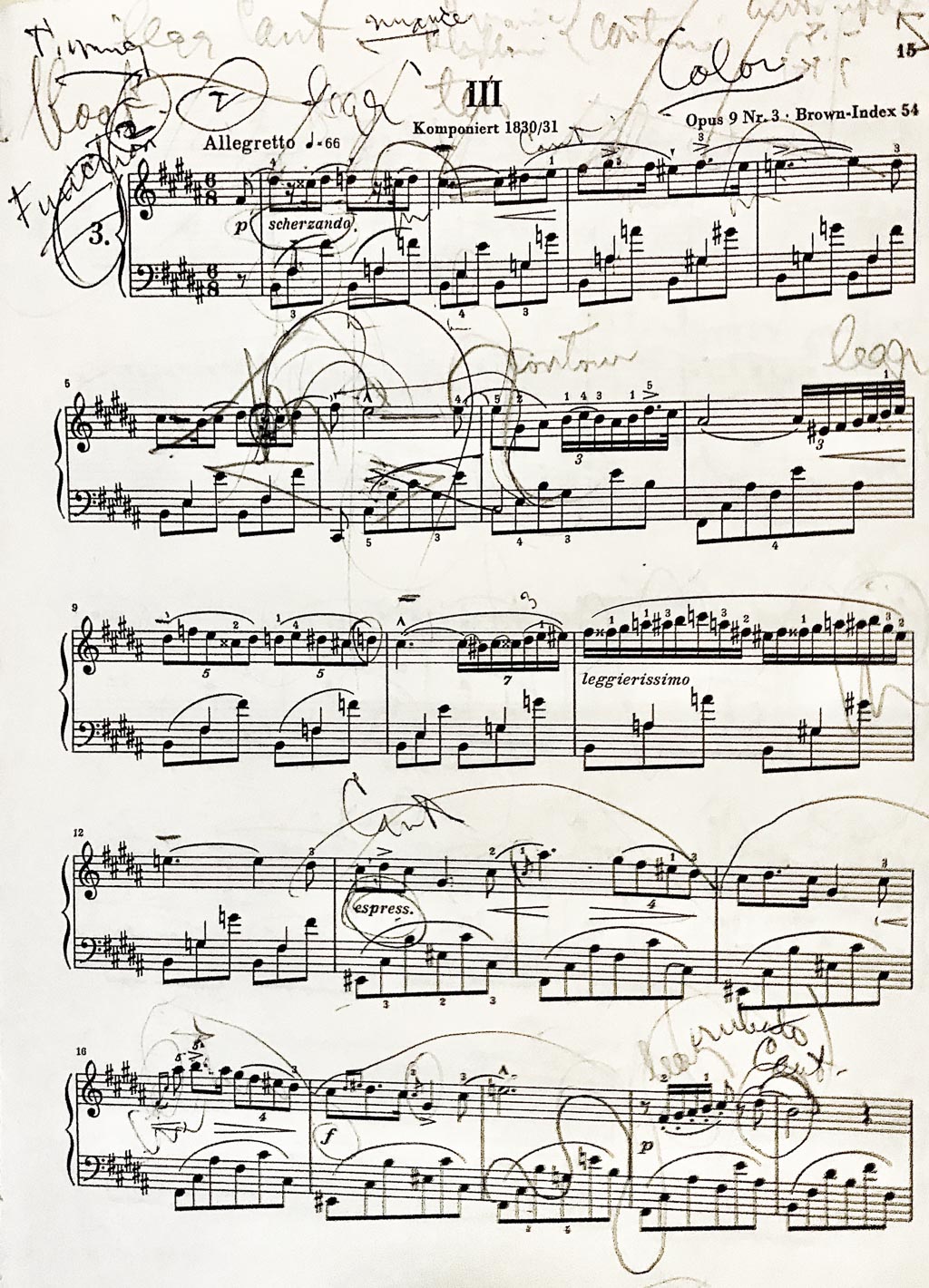

Chopin, Nocturne, Op. 9, no. 3

He has circled Chopin's instruction “scherzando”, which, I think, many performers miss—literally “joking” but here meaning “light-hearted”. I was just listening to a version by Anna Fedorova, who misses it by a mile. At m. 13 Chopin indicates a contrasting espressivo, and Harold's “Cant.” stands for cantabile again. I particularly like the wavy line above the left hand in mm. 18-19: even the left hand accompanying line has shape which demands definition.

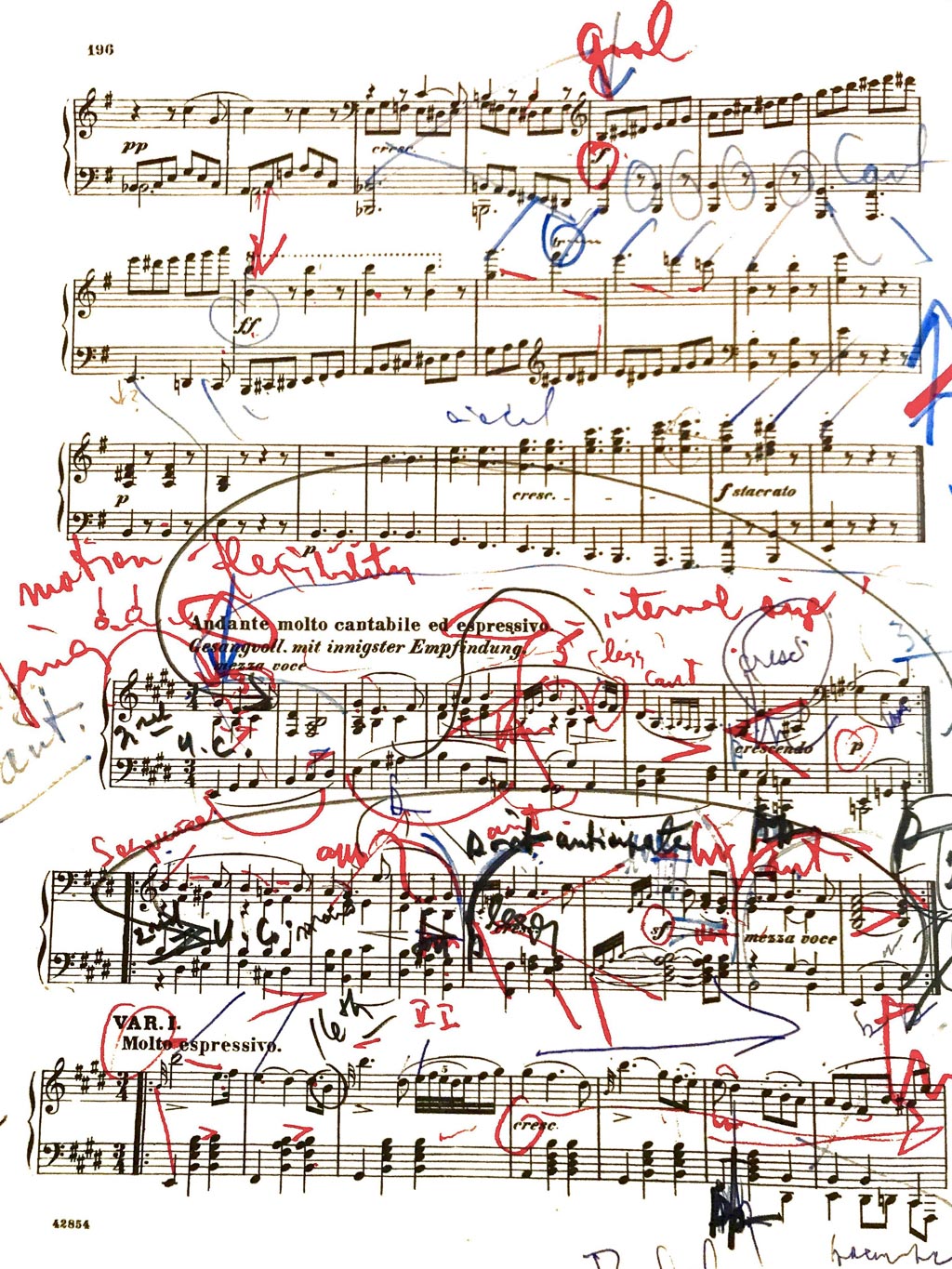

Beethoven, Sonata, Op. 109

This page shows the end of the second movement of the sonata, and the beginning of the third. From the density of Harold's notations, you can gather that the second movement is less problematic than the third. I just want to point out a bit of his attention to detail: at the end of the first line he has circled a number of eighth rests, drawing attention to the contrast between these notes and the next ones, where the notes are sustained, Beethoven wanting to hear their contrapuntal descent against the rising melody in the right hand.

The third movement is one of the most profound of Beethoven's slow movements. The notes are scarcely more difficult than the accompaniment to a Protestant hymn (to which the music is in fact related) but the challenges to the player are immense. “Motion” and “flexibility” in what is basically a steady succession of quarter-note chords; “interval size”—meaning that larger intervals demand fractionally greater weight; the counterpoint evident in the left-hand's rising line; a warning not to anticipate (rush); in the penultimate measure of the first line, where Beethoven has written crescendo, Harold has drawn a big red crescendo, and, since I evidently still didn't get the point, from a later lesson, a third “cresc.”, and as indicated by the big over-arching curved line, the whole first slow eight bars must sound like one long phrase. Each section is repeated, and Harold suggests the una corda for the repetitions.